Overview#

In this post, we’ll take a closer look at network virtualization - a topic that’s admittedly difficult, but definitely something you should understand at least once.

Basic Networking#

Before diving into network virtualization, let’s briefly review how a non-virtualized (bare-metal) network operates.

It’s very simple. A switch receives packets from the outside and forwards them to the server.

The server, in turn, uses a NIC (Network Interface Controller) to receive packets from the switch and deliver them to the kernel, enabling network communication.

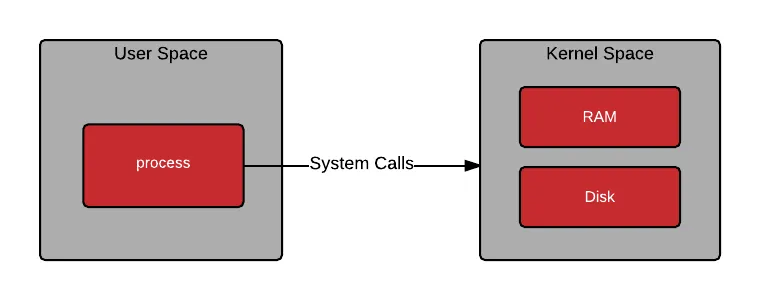

Internet - Physical Switch - Physical NIC - Host OSLinux divides memory into User Space and Kernel Space.

This strict separation prevents issues in one space from affecting the other, improving system stability and security.

User Space is where user-level programs such as processes and applications run.

Kernel Space is the core area responsible for hardware control and all critical system functions.

When the CPU executes user-level tasks, it operates in User Space.

If a task requires kernel-level privileges, execution switches from User Space to Kernel Space, a process known as a context switch.

While context switching is essential for system security and stability, it can lead to performance overhead.

One of the operations that frequently triggers context switches is network packet processing.

Virtual Networking#

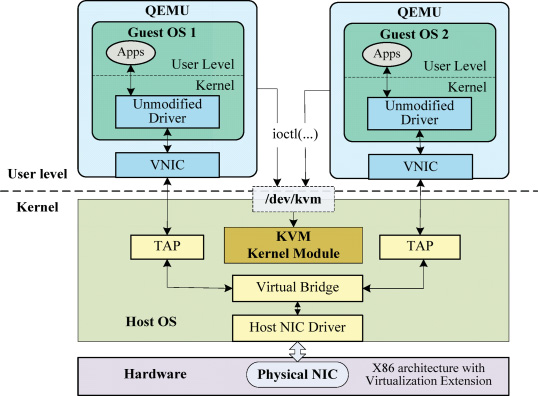

Now let’s look at how networking works in a KVM-based virtualization environment.

When a VM starts, libvirt creates a TAP interface, attaches it to a bridge, and connects it as the backend of the VM’s virtual NIC.

TAP(Terminal Access Point)/TUN(Tunnel)#

As their names suggest, both TAP and TUN are used for tunneling purposes.

They are virtual network drivers that control software-based virtual network devices.

Packets delivered to a TAP/TUN interface are forwarded to the connected user-space component (e.g., a virtual NIC).

In the opposite direction, packets are sent from user space to TAP/TUN and then passed into the OS network stack.

TAP(Terminal Access Point)

- L2

- Ethernet frames

TUN(Tunnel)

- L3

- IP packets

If you inspect the network interfaces on a host running KVM:

# ip a

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 ::1/128 scope host

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: enp3s0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc fq_codel master virbr0 state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether d8:bb:c1:74:e6:5a brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

3: virbr0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether d8:bb:c1:74:e6:5a brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 10.10.12.10/24 brd 10.10.12.255 scope global noprefixroute virbr0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

4: vnet0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue master virbr0 state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/ether fe:54:00:5f:b0:c0 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet6 fe80::fc54:ff:fe5f:b0c0/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft foreverYou can see:

- The physical NIC (

enp3s0) - A virtual bridge network for VMs (

virbr0) - A TAP device (

vnet0) that maps one-to-one with a VM’s virtual NIC

Although TAP interfaces operate via the TUN driver in Linux (so the driver appears as tun),

the bus-info field(which indicates where the device is attached on the system bus) shows it as a tap device.

# ethtool -i vnet0

driver: tun

version: 1.6

firmware-version:

expansion-rom-version:

bus-info: tap

supports-statistics: no

supports-test: no

supports-eeprom-access: no

supports-register-dump: no

supports-priv-flags: noBy contrast, a physical NIC reports a PCI address as its bus-info.

# ethtool -i enp3s0

driver: r8169

version: 5.14.0-162.6.1.el9_1.x86_64

firmware-version: rtl8125b-2_0.0.2 07/13/20

expansion-rom-version:

bus-info: 0000:03:00.0

supports-statistics: yes

supports-test: no

supports-eeprom-access: no

supports-register-dump: yes

supports-priv-flags: noAt this point, you should have a rough idea of how VM networking works.

Compared to bare metal, the original data path remains the same, but additional layers are introduced:

Internet - Physical Switch - Physical NIC - Host OS - Linux Bridge (or OVS) - TAP - QEMU/KVM - virtual NIC - VM OS

CPU Overhead#

Network packets must traverse multiple software layers before reaching a VM, which introduces CPU overhead, latency, and jitter.

- CPU usage by bridge, iptables, conntrack, etc.

- Context Switch (User space - Kernel space)

- Memory copies between QEMU, the kernel, and the guest

- CPU interrupts triggered on packet arrival

These issues stem from the architecture of the Linux networking stack, not virtualization itself.

However, virtualization increases software stack complexity, making these problems more pronounced compared to bare metal.

To address these overheads and meet the demands of modern high-speed networks, several technologies have been developed.

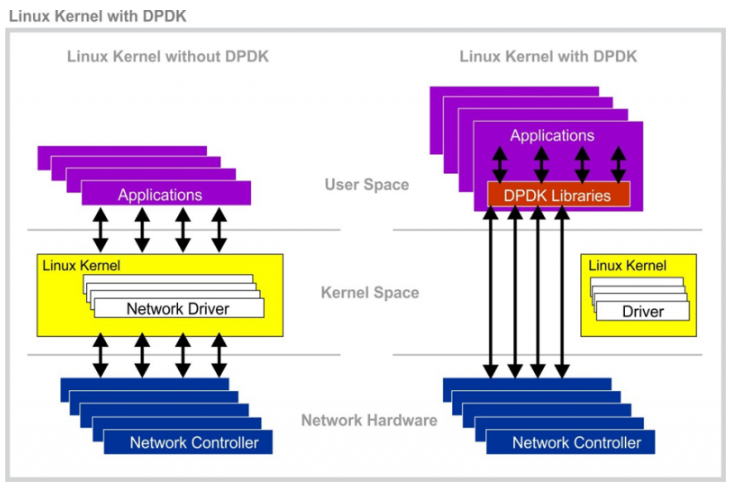

DPDK(Data Plane Development Kit)#

As NIC processing speeds have increased dramatically, packet processing within the operating system has failed to keep up.

DPDK was created to fundamentally change how packet processing is handled in the OS.

Its key feature is moving packet processing from Kernel Space to User Space, significantly reducing CPU overhead.

With DPDK, user applications can directly and exclusively control hardware without OS intervention.

In other words, it enables kernel bypass, increasing throughput and reducing latency.

However, bypassing the kernel means that the user application must process all Ethernet frames received by the NIC, which adds complexity.

For this reason, DPDK is commonly used when implementing high-performance routers, switches, and network monitoring systems in software—systems that must process tens of millions of packets per second.

DPDK-Based Virtualized Networking#

Let’s revisit virtualization from this perspective.

The simplified packet flow in a typical virtual network looks like this:

NIC

↓

Host kernel net stack

↓

TAP (vnetX)

↓

QEMU / KVM

↓

Guest kernel net stack

↓

Guest user appTo reach a user application inside the VM, packets must traverse two kernel network stacks, resulting in multiple context switches, memory copies, and interrupts.

DPDK bypasses the kernel networking stack and eliminates kernel copies via zero-copy techniques.

However, in virtualized environments using vSwitches or virtio-based networking, memory copies are still required, which can remain a source of CPU overhead.

When DPDK is used as an intermediate layer in virtualization:

NIC

↓ DMA

Host DPDK

↓ copy!!!

Guest virtio-net (Guest Memory)

↓

Guest kernel net stack

↓ copy (no copy when DPDK is used in guest)

Guest user appHere, the host kernel network stack is bypassed, and packet data is copied directly into guest memory.

Because the physical NIC and guest memory reside in different address spaces, DMA into guest memory is not possible.

As a result, even when using DPDK on the host, memory copies are unavoidable when delivering packets to the guest.

SR-IOV(Single Root I/O Virtualization)#

SR-IOV is a technology that improves server I/O performance by allowing multiple virtual machines to share a single PCIe I/O device while behaving as if each VM were directly connected to the NIC.

PF(Physical Function) : The physical PCIe device

VF(Virtual Function) : A virtual PCIe device; the number of VFs that can be created depends on the PF’s hardware specifications

To enable multiple VFs to operate on top of a single PF, the device internally uses queues to manage requests.

When a single queue is used, it is referred to as Single Root (SR), and when multiple queues are used, it is called MR-IOV (Multi-Root I/O Virtualization).

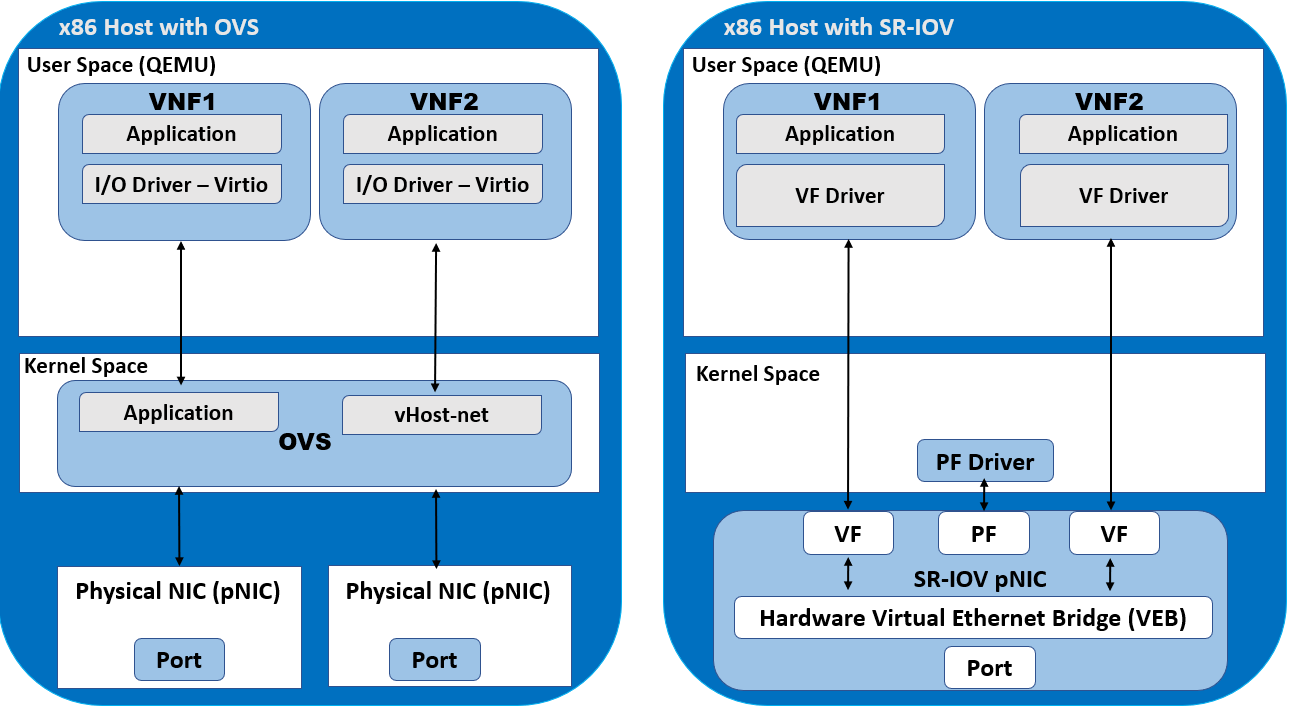

reference : SR-IOV, PCI Passthrough, and OVS-DPDK

As mentioned earlier, in a typical virtualized system, communication with a physical NIC requires traversing multiple layers.

Even when using DPDK, memory copies from the host to the guest are still required, which introduces overhead.

However, when SR-IOV is used to attach a VF directly to a VM, the NIC is effectively assigned directly to the VM, enabling the NIC to perform DMA directly into the VM’s memory.

At first glance, allowing a PCIe device to directly access memory via DMA may seem risky.

This is made safe by the IOMMU (Input-Output Memory Management Unit).

Refer -> MMU(Memory Management Unit) & IOMMU(Input Output Memory Management Unit)

By mapping only the memory addresses that each VF is allowed to access, the system prevents access to other VMs’ memory or host memory.

This isolation ensures that DMA operations can be performed safely.

vs PCI Passthrough#

Reference : PCI Passthrough

PCI Passthrough is another technique that assigns a PCI device directly to a VM without going through the host.

At a glance, it may seem similar to SR-IOV.

If an SR-IOV configuration exposes only a single VF, does that make it equivalent to PCI Passthrough?

The answer is no.

PCI Passthrough hands over the entire PCI device to the guest. As a result, the host can no longer control or manage the passed-through device.

In contrast, with SR-IOV, the host retains ownership of the PF while assigning only the VF to the guest.

The host still maintains control over the physical PCI device.

In summary:

- A VF is a logical port allocated within the virtualization layer, while the PF continues to exist and is managed by the host.

- With PCI Passthrough, the guest gains full and exclusive control over the entire device.